Introduction to Botanic Garden

The botanic garden of the University of Helsinki is part of the Finnish Museum of Natural History. The botanic garden, founded in Turku in 1678, is the oldest institution in Finland maintaining collections of natural history. In 1829, the garden, together with the University, moved to Helsinki and was re-established in its present location in Kaisaniemi. Nowadays, the garden also maintains premises in Kumpula.

An Old Manor in New Splendour

Welcome to the Kumpula Botanic Garden on the former grounds of Kumpula Manor!

Kumpula Manor is over 500 years old and is where, in the 18th century, Peter Forsskål grew up to become a student of Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern botany.

Since 1987, the University of Helsinki has been constructing a new botanic garden here to serve the research and teaching of botany – and to delight all fans of plants!

A century of botanic research, a quarter of a century of planning and building, hundreds of thousands of working hours, tens of thousands of seeds sown and seedlings nurtured…

A garden is never finished, but the Kumpula Botanic Garden is finally open for all to admire.

Join us on an expedition around the world in the spirit of botany!

Gumtäkt, Kumtähti, Kumpula – Pet Names for a Beloved Child

Kerstin Pedersdotter inherited the Kumpula estate from her husband, Olof Lydiksson, in the 1500s, when Finland was still part of the Swedish realm. In 1498, Kumpula became a manor estate when Pedersdotter was granted rälssi, a tax exemption used by the Swedish government to classify nobility. The manor was first known by the name of a village once situated in the same location: Gumtäkt, Gumtäckt or Gumteckt in Swedish, and later Gumtähti or Kumtähti in Finnish. The Finnish name Kumpula came into use in 1928, and Gumtäkt was established as the Swedish name.

Many families have owned the manor over the centuries. In the early days, the list of proprietors included the Jägerhorn, Jönsson, Påvelsson, Tavast, and Svanström families. It is an extraordinary coincidence that from 1733 to 1739, the manor was the property of Johannes Forsskål, whose son Peter (1732–63) became an apprentice of Carl Linnaeus, “the father of botany”. One of Finland’s most significant botanists grew up in an estate that was converted into a botanic garden 250 years later!

In 1840, the manor was bought by Baron Johan Gabriel von Bonsdorff, who had the three present-day manor buildings built between 1841 and 1844. The cellar located next to the main gate dates to the end of the 19th century, but the root cellars below the present-day medicinal plant garden are estimated to be a hundred years older.

The City of Helsinki bought Kumpula from Herman Standertskiöld-Nordenstam in 1893. The manor was rented to the National Board of Health in 1905 as an “additional venereal hospital” and continued to serve in this capacity until 1960. Before becoming state property, the manor was rented as an elementary school between 1962 and 1977.

Kumpula Botanic Garden – around the World in 80 Minutes

The old manor buildings are situated in the heart of Kumpula Botanic Garden. The main building is used by the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki. The customer service and office facilities of the botanic garden are located in the Upper Manor, which is the former stable. The third building serves as flats for the staff. A newly constructed outbuilding and maintenance area are situated next to the manor yard.

Construction of the greater part of the Kumpula plant collection area began in the 1980s on the basis of a design by landscape architect Gretel Hemgård. The collection comprises two parts:

- Hortus ethnobotanicus – the garden of cultivated plants

- Hortus geobotanicus – the geobotanical garden

The garden of cultivated plants includes both economic and ornamental species. There are separate sections for fruit and berry plants, other edible plants, and medicinal plants. The ornamental plants grow in the manor park and in the yard area near the buildings. The collection of cultivated plants comprises approximately 500 accessions representing 400 or so species or varieties.

The design of the geobotanical garden largely resembles an English landscape garden. The plants have been grouped according to their areas of origin into the following sections: Europe, eastern North America, western North America, the continental Far East, and Japan. In the Europe section, a separate part for Finland (Hortus Fennicus) is included, where planting will start in 2010. The geobotanical sections presently include over 1,500 plant accessions, together representing approximately 1,000 different species.

The Garden of Cultivated Plants – Hortus ethnobotanicus

Food and Eye Candy (not to Mention Clothes, Paper, Medication, and Tyres)

The human race is completely dependent upon plants. Hundreds of millions of years ago, plants developed the ability to bind the sun’s energy. They are, therefore, producers, the foundation of ecosystems.

We humans, in contrast, are consumers. We eat plants and feed them to our domestic animals. We use plants to build our dwellings, which we then heat with wood. We dress ourselves in clothes made of vegetable fibre. Plants have aided us in fighting myriad illnesses and ailments. We use plant products to beautify ourselves and for our hygiene. Plants provide us with industrial raw material and products, such as cellulose, paper, oils, rubber, resin, and glues, as well as dyes, perfumes , and pesticides. To top it all, plants even decorate our living surroundings, both indoors and outdoors – not to mention the fact that we would suffocate like fish out of water were it not for the oxygen plants produce.

Cultivated plants include both economic and ornamental plants. Humans learnt to cultivate land approximately 10,000 years ago. A species selected for cultivation by humans often undergoes a rather sudden change. Humans also began to purposefully breed cultivated plants very early on. The purpose of breeding is to strengthen the desirable qualities of a plant. For instance, we have enlarged or improved the taste of the edible parts of plants. We have also reduced harmful structures, such as thorns, which impede harvest. Cultivated plants altered by humans often clearly differ from their nearest wild relatives.

The Manor Park and Yard Area

Something Old But Mostly Something New, Something Borrowed from the Past

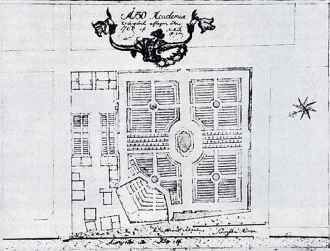

As far as is known, Kumpula manor never actually had a park before the time of Johan Gabriel von Bonsdorff (1840–72). Maps depicting the northwest side of the main building between 1891 and 1912 show a smallish English style manor park. The oldest trees in the area have survived from the 1900s; most of the trees, however, are from the time of the hospital (1905–60).

So at the time the botanic garden was being founded, Kumpula had no extensive historic manor park to restore. But the age of the current-day manor buildings has been taken into account in planning the ornamental plants section. The collection mainly comprises flora typical of manor surroundings in the 1800s. It includes ornamental plants which had found their way to Finland before the 1800s, such as common lilac (Syringa vulgaris) and hawthorn (Crataegus grayana), but mostly consists of species that spread throughout Finland during the era of Russian rule. The sturdy poplar (Populus balsamifera ’Hortensis’) on the west side of the main building is a typical example of such a plant, as is the plumleaf crabapple (Malus prunifolia) standing between the manor buildings. In the newer plantations, the same era is represented by mock-orange (Philadelphus coronarius), for example, and Burnet rose (Rosa pimpinellifolia).

The Kumpula bush rose collection is a sort of live gene bank, because it includes numerous species and varieties which have traditionally been grown in Finland, but of which some have become rare. Old varieties can endure the erratic weather conditions in Finland, even though they blossom for a considerably shorter time than new, bred varieties.

One end of the manor park is a rock garden. Rock gardens became fashionable in Europe approximately 200 years ago. According to current information, Finland’s first rock garden was established in Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden in 1884. This trend soon began to spread to manors of Finland.

The Medicinal Garden

Problems with Parasites and Aches All Over? Remedies for Many Ailments

The medicinal garden is where the botanic garden goes back to its roots. In 1678, Professor Elias Tillandz obtained permission from the consistory of the Royal Academy of Turku to fence in the herbal garden used for teaching and, thus, established a botanic garden. Precisely what plants the Academy garden contained then remains unknown, but the collection likely included many of the same species that currently grow in the Kumpula medicinal garden; botanic gardens were originally significant for their role in teaching medicine.

The medicinal garden is where the botanic garden goes back to its roots. In 1678, Professor Elias Tillandz obtained permission from the consistory of the Royal Academy of Turku to fence in the herbal garden used for teaching and, thus, established a botanic garden. Precisely what plants the Academy garden contained then remains unknown, but the collection likely included many of the same species that currently grow in the Kumpula medicinal garden; botanic gardens were originally significant for their role in teaching medicine.

Also the display order of the medicinal plant collection may resemble that of the original academic garden. The plants have been grouped according to their purposes of use. There are separate sections for plants which improve immune response and general health, reduce respiratory problems, are used for skin care, alleviate pain, nurture mucous membranes, help to get rid of parasites, cure women’s diseases, affect moods, are used for cardiovascular diseases, improve stomach functions and digestion, or affect the urinary tract and urine excretion. Centuries of research have nonetheless proven many belief-based plant usages ineffective. Consequently, the usage-based grouping has also been changed.

The hawthorn hedge around the medicinal garden also fences in a selection of other economic plants. Included are examples of stimulant, honey, and aromatic plants, dye, oil, and fibre plants, and fodder crops. The collection is by no means comprehensive: over 7,000 plant species worldwide have seen regular use just in human nutrition, and tens of thousands of species are being used in different ways!

Food Plants

Where Did the First Carrot, Cabbage, or Courgette Grow?

Food plants growing in straight patches give this section of the garden a traditional kitchen garden feel. Most of the vegetables, legumes, root crops and various aromatic herbs are annual. The variety of species here gets the best of most vegetable patches: the collection includes approximately 200 different plants, i.e., most of the species that can produce a harvest in open land in Finland. The selection includes agricultural field plants, such as different kinds of cereals and the sugar beet, and many species that cannot be cost-effectively cultivated on a large scale in Finland.

The food plants have been grouped according to the part of world where they were first taken into cultivation, i.e., domesticated. When viewed from down to up, the domestication areas seem to mirror a world map. North, Central, and South America are located on the left, and Europe and North Asia in the middle. Below them lie the Mediterranean region, the Middle East and Central Asia, and finally Africa and West Asia. On the right hand side grow the species domesticated in East or Southeast Asia, and below them is New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides), said to have been what captain Cook fed his crew in order to prevent the scurvy.

We humans are curious by nature and for thousands of years have learnt to eat a tremendous variety of offerings of the vegetable kingdom. The plant parts we use for nutrition include leaves, petioles, seeds, fruits, stems, rhizomes, roots, bulbs, and even inflorescences or flowers! Can you find an example of all these in our food plant collection?

The Fruit and Berry Garden

The Juicy Harvest of Trees and Shrubs

When facing southeast at the garden gate, you will see a view that has changed little over the centuries. The road, now called Jyrängöntie Road, has not altered its course, nor has the manor house behind your back moved from its location. Only the sea that glistens far off in the horizon used to be closer, before the rebound of the land and the extensive filling of inner bays. A spinney of deciduous trees covers the upper hillside alongside the road. The sunny lower hillside is rich in soil and under cultivation just as it apparently was already in the 1400s. It used to be a cultivated field, but is now a fruit garden. At least in the 1800s, the fruit garden was situated on the hillside north of the manor house, where there is now a meadow.

Surprisingly, many fruit trees manage to endure the climate in the southernmost parts of Finland. When planted on a favourable warm hillside, such as the one described above, many varieties of apple produce a harvest, as do plum, damson, pear, sour cherry, and wild cherry trees. For Finns, the least familiar plant in this collection is the shrub-like Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica), which produces a sour fruit used for jam and juice.

The black, red, and white currants and the gooseberry are familiar to Finns, but Finland also offers suitable conditions for growing green currant and the hybrid jostaberry. The chokeberry has been a popular ornamental plant in Finland during the past few decades, but the species has also been bred into many berry varieties. The former Soviet Union actively bred new berry plants, such as the blueberried honeysuckle and the highbush blueberry. In future, Kumpula will also provide the opportunity to see crop-bearing Saskatoon serviceberry trees, cranberries, strawberries, and cloudberries.

The Geobotanical Garden

Wild-collected Plants from Finnish Climates around the World

None of the plants in the Kumpula geobotanical collection have been acquired from plantations. They have been collected directly from their natural habitats. This makes our collection unique on a worldwide scale and renders it extremely valuable from the viewpoints of research and the conservation of endangered species. The planting process in these sections began in the mid-1980s, and 2,492 accessions have been planted since, 1,533 of which are still alive. A lot of sweat and even a few tears have gone into obtaining these plants!

Plant Hunting in the Spirit of Indiana Jones

The head of the botanic garden of the Academy of Turku, Professor Peter Kalm, travelled to North America in 1747. After a three-year stay he brought back hundreds of plants, which, however, failed to thrive. Only three species still grown in Finland can be considered the fruits of Kalm’s journey: hawthorn (Crataegus grayana), woodbine (Parthenocissus inserta) and purple‑flowering raspberry (Rubus odoratus).

The head of the botanic garden of the Academy of Turku, Professor Peter Kalm, travelled to North America in 1747. After a three-year stay he brought back hundreds of plants, which, however, failed to thrive. Only three species still grown in Finland can be considered the fruits of Kalm’s journey: hawthorn (Crataegus grayana), woodbine (Parthenocissus inserta) and purple‑flowering raspberry (Rubus odoratus).

In order to compile the Kumpula collection, Professor Timo Koponen, head of the garden between 1992 and 2001, followed the example set by Kalm 250 years earlier. He gathered his troops and embarked on a quest. His group made three seed collecting expeditions in the early 1990s: one to Hokkaido, Japan (-93), one to Northeast China (-94), and one to Western Canada (-95). These and other, shorter, journeys have provided approximately 40% of the plant accessions in the geobotanical sections. The rest have been acquired mostly through seed exchange with other botanic gardens when material collected from the wild has been available.

Successful plant hunting requires persistent research work before dashing off into the wild. Just like an archaeologist in search of prehistoric treasures, a botanist must know where to search for what. Plenty of information has been accumulated since the days of Kalm; over half of the haul of Koponen’s excursions was viable and now flourishes in Kumpula!

The Climate of Helsinki Elsewhere in the World

Traditionally, botanic garden collections are grouped according to plant relatedness. For example, different species of pine are placed in one section, and birch trees in another. A more modern method is to display the flora of a particular region by planting the plants originating from there side by side. This is the model followed in the Kumpula geobotanical collection.

Traditionally, botanic garden collections are grouped according to plant relatedness. For example, different species of pine are placed in one section, and birch trees in another. A more modern method is to display the flora of a particular region by planting the plants originating from there side by side. This is the model followed in the Kumpula geobotanical collection.

For over a hundred years, Finnish scientists have studied the relationship between the climate and the occurrence of plants. They have compared average and extreme temperatures, rainfall, the rhythm of the seasons and other climate-related factors. Thus, they have been able to define those areas of the world where the climate more or less corresponds to that of Southern Finland; cold and harsh, as is typical of the North, but occasionally mild even in wintertime due to the proximity of the ocean. These climatic counterparts of Southern Finland exist at the fringes of continents, mostly in latitudes further south than Finland, and in some temperate mountains.

Sections Organised Carefully According to Counterparts

The hortus geobotanicus rises from a bed of clay that used to be the seafloor at the bottom of Vallilanlaakso valley. It creeps up the moraine on a gentle southern slope and climbs onto a rocky hillock in the northern part of the garden. Finally, it reaches the man-made mounds of earth in the former location of the garden’s nursery. The geobotanical garden has been divided into sections according to the climatic counterparts of Finland.

The sections spread out like a fan from the pond onto the rock outcrops. This way it is possible to grow wetland plants as well as forest and meadow species in all the sections. ‘Europe’ begins from the southern side of the pond and meanders towards the manor park. Finland spreads out onto the slope on the south side of the main building. Strips of lawn form an imaginary Atlantic Ocean separating Europe from eastern North America. On the other side of the next grass zone looms western North America. It is bordered by a narrow passage of lawn representing the Pacific Ocean, which marks the beginning of the Far East section. It curves northward from the pond along the brook. Japan begins on the opposite shore of the brook and covers the entire west end of the garden. In 2010, we will begin collecting plants for the hills on the northern side of the garden and for the collection of Finnish plants.